TIP OF THE SPEAR

4 Levels of Performance

BY DOC SPEARS

I regret not having a formal education in philosophy. After my army service, my time in college was spent fervently trying to knock out the necessary credits to continue on to a professional degree. I could’ve taken extra courses during the pursuit of my bachelor’s, but instead spent too much time in the dojo and in the gym. I nonetheless managed to advance and eventually achieve my goal of avoiding poverty (though I pined for the life I left and all my brothers back on an A-Team.)

My motto: whatever you do, you’ll regret it.

By self-study I’ve maybe caught myself up in several areas of basic knowledge that I missed in college, but philosophy is certainly the one foundational field I regret not getting a better exposure to much earlier in life.

Epistemology is the branch concerned with learning. My favorite encapsulation of that big word is simply this; how we learn to distinguish between opinion and justified belief. IMO, if more people considered how they form beliefs about themselves and the larger world, the world would be a better place.

As it relates to the subject of learning mind-body skills, (like marksmanship—what I seem to be writing most about here for Wargate) how we assess our own levels of competence is a part of that process. And having some understanding of the process of learning any skill is vital to progressing in any training and practice.

So if you’ve never been exposed to a guide or framework for evaluating yourself as you attempt to learn and progress in a skill, then this is worth your time. For your consideration, I present, (drumroll, please)…

The 4 Levels of Performance.

Unconscious Incompetence

Conscious Incompetence

Conscious Competence

Unconscious Competence

I’ll illustrate each level with the typical performance that describes it. If you care nothing about shooting, keep in mind these apply to the process of developing any mind-body skill.

Unconscious Incompetence

A guy buys a gun. He goes to the range. He has little or no formal training. He manages to do what the other shooters seem to be doing; load, shoot, maybe hit something. He doesn’t know how he’s done what he’s done, but he hasn’t injured himself or anyone else, and considers it a successful outing and himself, competent.

Conscious Incompetence

Same guy goes to the range again. He notices the shooter next to him. The size of that person’s groups on target is noticeably smaller than his. That person is seemingly manipulating the weapon with ease and pleasure. He asks the better shooter for advice and during that range session, he has a realization; he doesn’t know what he’s doing.

He decides he needs… TRAINING!

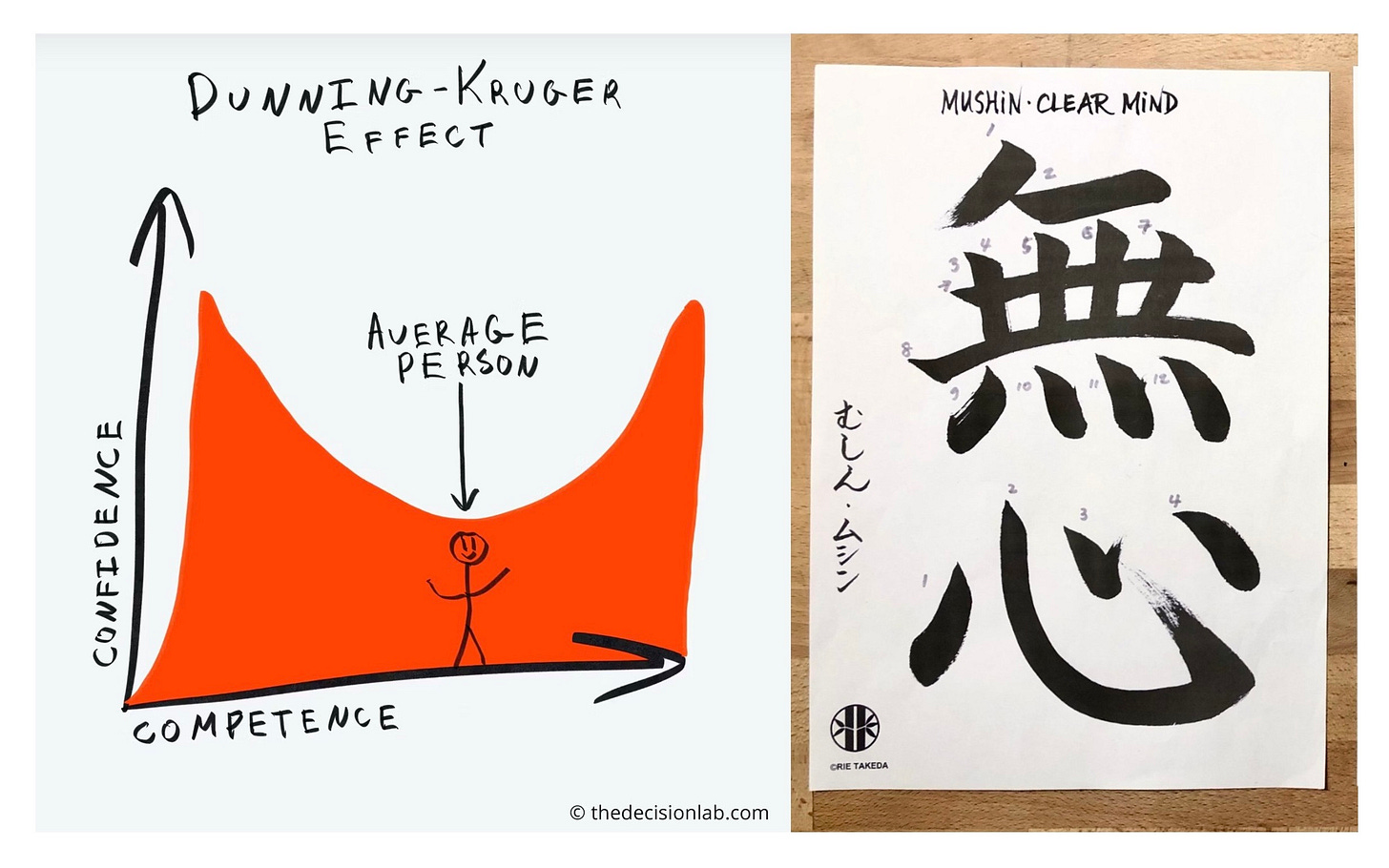

Reaching performance level #2 is very important. It’s a defining moment, where true self-awareness is evidenced. When it doesn’t, we have the prime example of a person identified by the meta-cognitive disorder known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. If you’re unfamiliar, it’s a psychological phenomenon where unskilled people believe they are in fact highly skilled, and no amount of objective evidence can convince them otherwise.

We’ve all known a person who suffers from that disorder, and they’re the very definition of difficult to work with. If you’ve ever heard someone say, “that guy’s a D-K,” I hope they weren’t referring to you.

As an aside, I find the other, smaller subset of D-K sufferers to be the most interesting; where highly skilled and knowledgeable individuals believe themselves to be of lower ability, because they believe others are equally competent and appreciate the complexities of the task. There’s a fine line between humility and being under confident.

Conscious Competence

Our new shooter got some formal training, maybe through a program at the local gun club, or he travelled to where a reputable trainer offers courses. This required effort. As a result, he now knows how to perform the fundamentals of shooting; like stance control, grip control, sight control, breath control, trigger control, follow-through, and calling the shot. BUT! With each shot, he must think to direct how those elements are performed. When he doesn’t, he fails. As his awareness of the process increases, perhaps he learns to self-coach and identify and correct a deficiency responsible for a poor result.

Level #3 is a wonderful place to be, and progress is sure to occur. Eventually, that leads to…

Unconscious Competence

The conscious mind is the director of action. The unconscious mind is where the repository of mind-body skills lives; like a complex computer program waiting to execute its function on command. I’ll leave the example of shooting for a moment and use an illustration everyone can relate to: the act of driving a car.

When you first learn to drive, every act is a consciously directed one. Once a body of confident skills are built, you don’t have to think how to turn the wheel or do anything else. Your conscious mind sets the destination, and your unconscious mind operates the vehicle.

To build an engram—the neural imprint that is the captured memory of how to perform a complex task—it requires hundreds of correct repetitions. (Which is a subject for another blog.)

Another aside—have you ever taught your kid to drive? I taught my four children. With each, I questioned if I dropped them on their heads too many times as an infant or if they (or me) actually knew English. I’ve never questioned my instructional abilities or their IQs more than during those first times letting them behind the wheel. Remember your own experience as a student driver. The initial combination of the environment and the on-demand actions required can be overwhelming.

I’ll contrast teaching a kid to drive with my other job; training professionals in the use of firearms and their applications to solving problems. With a shooter already competent at basic marksmanship, when you put them in a helmet and plate carrier and then add firearms to the package, they behave as if their verbal comprehension and mental processing ability has suffered a 20 point IQ drop. When their faculties recover and that person advances to attend a basic shoothouse course, even after many hours in the shoothouse of dry-practice, the first day of live-fire, their IQ drops 40 points.

Of the two, teaching a kid to drive is harder, and maybe more dangerous. So if you’ve successfully taught a kid to drive, you might find relief in a second career teaching CQB.

The last I’ll say about that highest level of performance, relates to the essence of what a school of discipline like Zen Buddhism ultimately tries to teach. It’s what the swordsman and author of The Book Of Five Rings, Miyamoto Musashi, discusses in the Void Book: a mind free from fixation and distraction. In Western terms, it’s simply the clarity to perform without conscious thought. It’s one of the many, many benefits resulting from the adoption of a thoughtful practice of marksmanship.

And by learning “how to learn” one thing, you can learn others.

Yes, there are other vehicles for this type of journey, but marksmanship is the one I extol as uniquely available to you as a person living in a country founded on liberty. I don’t mean to beat a dead horse, but I’m on a lifelong mission: to inspire others that when considering self-improvement, owning a firearm and being competent with it—and there is a difference—can be part of a transcendent practice.

The study of marksmanship can provide benefits far beyond the ostensibly satisfying experience of shooting accurate groups. Since it’s a path that requires self-discipline, it’s a means for pursuing metaphysical change, and provides mutual benefit to you and to society as a whole. That is, if you allow yourself to become conscious of the higher calling to be more than just a gun owner.

My version of the saying goes like this; climb the treasure mountain, and you will not return empty handed.