TIP OF THE SPEAR

Revisionist History Never Rusts

Eighty years of revisionist lies about our only nuclear war.

BY DOC SPEARS

“Pacifism is a shifty doctrine under which a man accepts the benefits of the social group without being willing to pay—and claims a halo for his dishonesty.” (Robert. A Heinlein, Starship Troopers, 1959.

I’m not implying that anyone against the use of nuclear weapons is by association necessarily a pacifist. The world must never again see the use of nuclear weapons. The excellent military affairs and intelligence journalist Annie Jacobsen in her book Nuclear War: A Scenario, makes a compelling case that in our current age, a contained and limited nuclear engagement is impossible. If fusion bombs start melting cities, worldwide extermination is the end point.

Instead, what I’m stating is that the infinity-loop of revisionist history claiming the use of the atom bomb to end our war with Imperial Japan was unnecessary, well, it’s dishonesty defined. And those who wield that argument are indeed cloaking themselves in fake virtue, like the pacifist described by RAH.

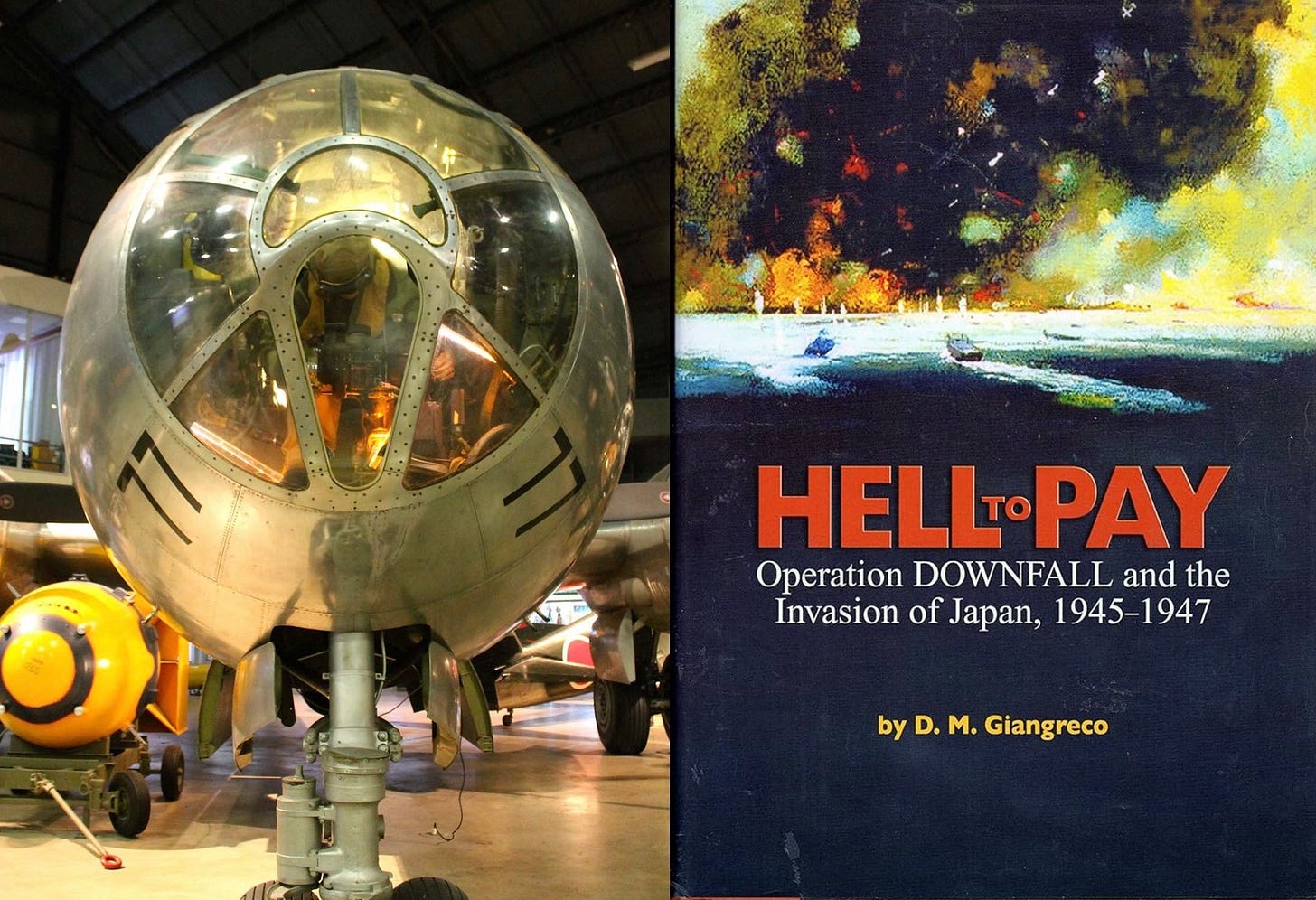

Whenever the topic presents regarding the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and the staggering loss of life they produced—both the instantaneous and the perhaps more dreadfully delayed deaths by radiation, which totaled 150,000-200,000 by the end of 1945—I’m always first to draw the fight stopper; the book pictured above.

D.M. Giangreco’s Hell to Pay: Operation DOWNFALL and the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1947, is the big iron on the hip of the rhetorical gunfighter willing to step up and defend intellectual honesty in the debate regarding how our war ended with Imperial Japan.

Giangreco’s scholarship is unassailable.

By themselves the numbers he presents paint a picture that would seem to answer for any reasonable person the question of what one would do had they been in President Truman’s position, calculating the human cost of an invasion of Japan.

The invasion of Japan was planned in two phases; Operation Olympic targeting the southern island of Kyushu and Operation Coronet the invasion of the largest island of Honshu. But by this point during the 1944-1945 casualty surge in Europe and the western Pacific, the U.S. Army was experiencing 65,000 killed, wounded, or missing every month. To prepare for DOWNFALL would’ve required a draft of up to 900,000 new inductions into the Army and Navy.

In the closing months of the war in East Asia and the western Pacific, as a result of Japan’s aggression, 400,000 people died in each of those months—soldier, civilian; man, woman, and child. The military historian Victor Davis Hansen often quotes the figure of 10,000 deaths per day, a more easily recalled and similar sum to describe the death toll realized during the entirety of the Pacific campaign.

The sheer magnitude of those numbers alone should serve to accurately convey the existential dread that must’ve been felt by anyone in 1945 contemplating a continued war with Japan.

Revisionists power their arguments against the rapid end to the war by nuclear bombardment through the false belief that Japan was on their last legs; that they were on the verge of surrender. Again, I leave it to Giangreco’s scholarship to definitively prove the lack of honesty behind such rhetoric. The evidence is ample that the Japanese would be able to mobilize millions of soldiers and civilian militia against a force invading their homeland.

The April to June, 1945 invasion of Okinawa cost over 12,000 American lives and many times that wounded. The Japanese wasted 150,000 military and Okinawan civilian lives to defend the small island—only sixty miles long and a third as wide—using fanatical tactics like kamikaze attacks, human torpedoes, and suicide boats. Fueled by ample reserves of armaments, what level of fanaticism could reasonably be intuited would be used to defend the much larger Japan?

Giangreco’s research proves beyond a doubt the sobering expectations of what an invasion of Japan would cost in human lives. It was estimated that Operation DOWNFALL would create as many as one million U.S. casualties, perhaps three to five million in Japanese defenders, and conceivably take until 1947 to achieve victory.

Approximately 1.5 million Purple Heart medals were produced in WWII, with a half-million of those ordered specifically in preparation for DOWNFALL. It is true that newer productions of the Purple Heart medal have been made, but it is also verifiably true that medals from the production for DOWNFALL are today still being issued from surplus stocks, miraculously created by the atomic bombings and Japan’s subsequent surrender.

For all of these reasons, it is why whenever the topic comes up on social media, if you follow me, you’ll see that I simply post a picture of the book cover above. Those that have read it heartily agree it is the ultimate back-stop to revisionist history concerning Truman’s use of the atom bombs, and I hope my pithy posting of just the cover and the number of positive reactions it receives inspires new readers to take it up.

The book came out in 2009, but was essentially a response to the debacle associated with the 1995 50th Anniversary exhibit of the Enola Gay at the National Air and Space Museum—cancelled by the revisionists and only later reconstituted in a form that emphasized the aircraft, not the role it played.

Veteran’s groups were told by the revisionists that they, “misremembered,” the one-million-anticipated casualty figure, and that no evidence ever existed that Japan had the ability to provide any real resistance to an amphibious invasion. Instead, the decision to use the atomic bomb had racist motivations, and the bombs were used primarily to send a message to the Soviets.

James Michener was at the time perhaps the best known writer in the world. He was a witness to history as he was an Army veteran of Saipan and Okinawa, poised to participate in the invasion of Japan. Michener was asked to address the issue of Truman’s atom bomb decision as it was initially meant to be presented in the Enola Gay exhibit.

Michener declined, fearful of the reaction by the literary and Hollywood circles he moved. However, he wrote a letter addressing the issue, asking only that it not be made public until after his death. He never took a side against the use of the atomic bombs, but not until his death were his views made public supporting the decision to end the war by a nuclear campaign.

To quote; “How did we react? (to learning the bombs had been dropped) “With a gigantic sigh of relief.”

Near the end of his letter he said he was able to, “take refuge in the terrible, time-tested truism that war is war, and if you are unlucky enough to become engaged in one, you better not lose it.” He finished by saying, “I accept the military estimates that at least 1 million lives were saved, and mine could have been one of them.”

Yes, dropping the atomic bombs saved at least a million lives. It may even be the reason you are able to read this.